In response to the Federal Trade Commission’s consideration of a rulemaking related to deceptive or unfair environmental claims under the FTC Act, I strongly concur with this initiative. The goal of the Green Guides is to help marketers avoid making misleading environmental marketing claims to protect consumers and inhabitants of our planet. However, with current guidance being relatively unknown in the marketing field and unenforced at the organizational level, that regulatory objective is not being adequately addressed.

Uninformed greenwashing practices continue to create monetary damage for consumers. Greenhushing, a relatively recent development whereby marketers avoid any language related to their company’s sustainability initiatives, demonstrates confusion and fear around the consequences of making potentially false statements. Neither marketers nor consumers are satisfied or protected tangibly with the current Green Guides, and therefore a more comprehensive and strict rulemaking is needed to enhance accountability and education on all fronts.

The ultimate objective of the Guides cannot be achieved exclusively through recommendations that are 1) optional and 2) exclusively targeted toward marketing departments. Responsible communication around sustainability requires a whole enterprise shift, such that marketing departments are able to accurately advertise green products, but those products must be designed to authentically fulfill green standards in the first place (i.e., carbon neutral, zero waste, etc.).

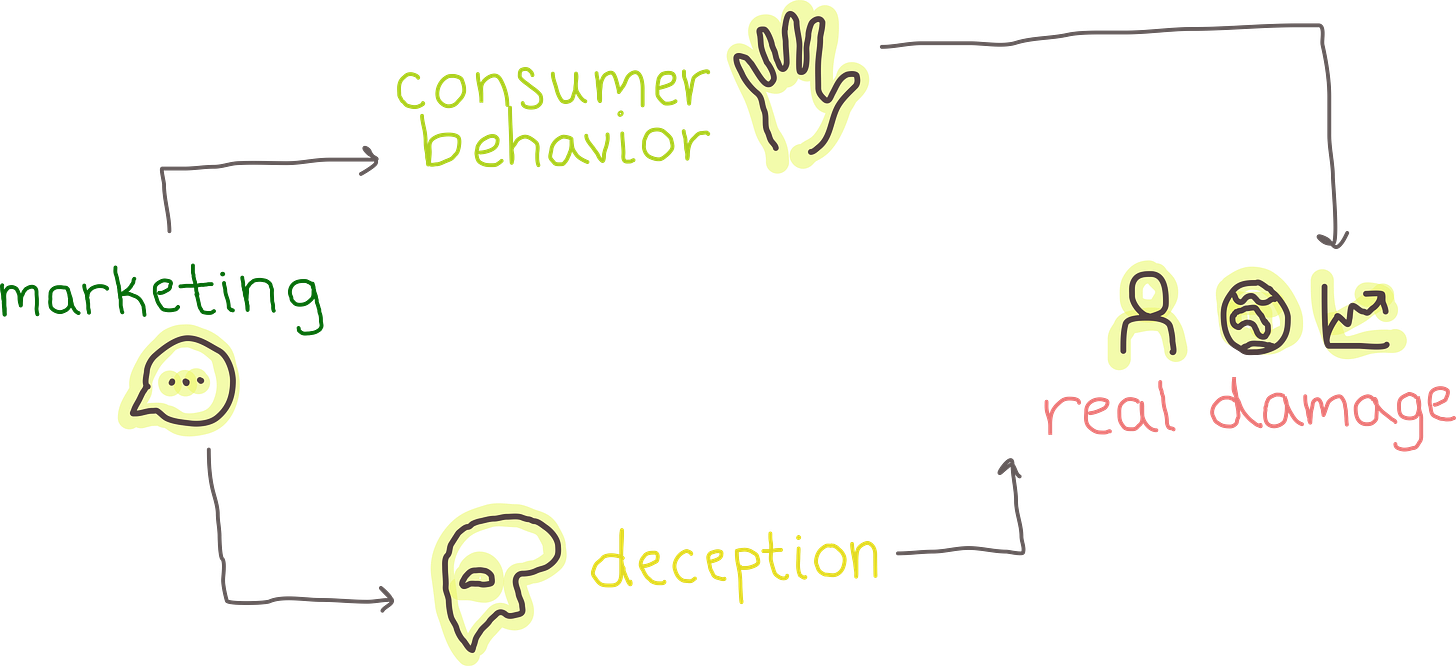

An expanded scope and stricter enforcement for the Green Guides is needed because 1) current marketing techniques are deceptive, 2) consumer behavior is influenced by environmental marketing, creating real damage for buyers, and 3) green marketing is more than just claims on a package or advertisement.

Current environmental marketing techniques are deceptive.

Demand for more sustainable products and services is a priority for many groups of stakeholders, from investors to employees to customers to supply chain, which has lead some companies to charge forward using “green” language without full knowledge of its implications. The European Commission found in a 2020 assessment of a broad range of industries that 53.3 percent of products “provided vague, misleading, or unfounded information” about their environmental impact, and 40 percent had no supporting evidence at all.

According to the 2012 Green Guides, an “overstatement of environmental attributes” is one of the general principles qualifying misleading environmental claims.

Another term for this phenomenon is greenwashing, of which there are many varieties executed by various organizational types. A spectrum exists of unintentional greenwashers, intentional greenwashers (or ‘evil greeners’), truthful green marketers, and green blushers. As they are currently written, the Green Guides appeal to truthful green marketers and green blushers, who proactively go out of their way to accurately communicate their sustainability initiatives, because the guidelines do not carry implicit regulatory weight. Because of this, intentional and unintentional greenwashing still exists in the following forms, along with many others:

Green spinning: when a company presents its own version of environmental facts

Green selling: when a company includes environmental benefits inherent to a traditional product in its marketing

Green harvesting: when a company decreases costs thanks to a sustainable practice but sells product at a premium price to earn extra profits

Each of these forms of greenwashing should be discussed in the Green Guides. Additionally, even when information presented is scientifically or third-party verified, such as with regulated product certifications, there still may be uncertainty as to “which products can be hazardous to people or the environment long after the sale has been made.” Inherent risk in forward-looking statements, along with misleading claims due to environmental education gaps and intents to capitalize on sustainability, have created an atmosphere of deception for consumers. Without a more rigorous FTC Rule, consumers will continue to experience real damage inflicted by industries that remain more or less unregulated in environmental marketing.

Consumer behavior is influenced by environmental marketing, causing buyers to experience real damage.

According to the 2012 Green Guides: “a representation, omission, or practice is deceptive if it is likely to mislead consumers acting reasonably under the circumstances and is material to consumers’ decisions.”

To explain the process of consumer deception and its impact on decision-making, the literature on environmental marketing has frequently cited the stimulus-organism-response model as a psychological mechanism influencing green consumer behavior. Specifically, stimulus elements such as eco-labeling and green advertising impact green customer-based brand equity, which combined with green product perceived quality, green image, and green trust, influences purchasing behavior.

Compared to historical purchasing drivers in the U.S. which primarily included product performance, consumer materiality is now influenced by “green marketing elements such as product features, quality, origin, taste, price, packaging, labeling, durability, service, or whatever environmental features might satisfy [the consumer].”

The decision to buy products, which are often more expensive, based on their environmental benefits can create real monetary damage for consumers when the claims are unfounded or unfulfilled. Consumer happiness, trust, and pocketbooks are all impacted by green marketing, representing a material need to actively regulate the validity of environmental marketing claims. A stricter rulemaking by the FTC could help redress consumer damages, and do so by engaging beyond just enterprise marketing departments.

Green marketing is more than just claims on a package or advertisement.

According to the 2012 Green Guides: “The guides apply to environmental claims in labeling, advertising, promotional materials, and all other forms of marketing in any medium, whether asserted directly or by implication, through words, symbols, logos, depictions, product brand names, or any other means.”

In the modern economy, environmental marketing is defined by “strategic, tactical, and operational marketing activities and processes that have a holistic objective of creating, communicating, and delivering products with minimal environmental impact.”

Strategic activities include analyzing the growth market, assessing consumer behavior, and delegating budget toward green products or campaigns.

Tactical activities include actions related to the traditional marketing mix or 4 P’s (i.e., product, price, placement, promotion), which requires the input of supply chain and logistics, product designers, financial analysts, and many other company departments.

Operational activities include short-term activities to drive sales, which are driven by deeper environmental and social company values.

Setting green missions and goals, green branding and segmentation, delivering and promoting green products, and eco-design all fall within these core marketing activities, and most of them are not directly addressed in the Green Guides.

Many of these processes and activities considered under “all forms of marketing” require intervention in marketing strategy that subsequently influences internal environmental operations of firms, including 1) green suppliers, 2) environmental resource management, 3) green research and development, and 4) environmental manufacturing processes and procedures. Researchers encourage marketers to cover “the full environmental costs of production and consumption [needed] to create a sustainable economy,” which requires engagement and strategy far beyond the marketing department.

In short, in order to environmentally market in a responsible way, there must be a shift in company internal operations–from product design to supply chain to company finance–to determine whether or not claims are accurate against the “clear and competent scientific evidence” standard. A clear pathway for company communications is not currently included in the Guides, but it could be if the standards were more strictly enforced and all-encompassing.

For example, if information on suppliers, product design, and company policies were called out as relevant to marketing claims in the Green Guides and they became legally binding, the likeliness of organizations paying attention to these guidelines would dramatically increase.

Overall, as a result of shortcomings with the current Green Guides in terms of their clarity, scope, effectiveness, and adoption, a rulemaking by the FTC is a critical next step for putting the Green Guides into action to protect consumers.

References

Dangelico, R. M. & Vocalelli, D. (2017). “Green marketing”: An analysis of definitions, strategy steps, and tools through a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Cleaner Production, 165, 1263-1279. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.07.184

D'Souza, C., Taghian, M., Sullivan-Mort, G. & Gilmore, A. (2015). An evaluation of the role of Green Marketing and a firm’s internal practices for Environmental Sustainability. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 23(7), 600-615. doi:10.1080/0965254x.2014.1001866

Ganimete Podvorica, Fatos Ukaj. (2019). The Role of Consumers' Behaviour in Applying Green Marketing: An Economic Analysis of the Non-alcoholic Beverages Industry in Kosova. Wroclaw Review of Law, Administration & Economics, Vol 9:1,/DOI: 10.1515/wrlae-2018-0061/Sciendo.

Howarth, T. (2023, April 4). The new EU law that's looking to stamp out greenwashing. GreenBiz. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

Gázquez-Abad, J. C., Jiménez-Guerrero, J. F., Mondéjar-Jiménez, J. A., & Cordente-Rodríguez, M. (2011). How companies integrate environmental issues into their marketing strategies. Environmental Engineering & Management Journal, 10(12), 1809–1820.

Rastogi, P. (2014). A Critical Evaluation and Analysis of Green Marketing. International Journal of Managerial Studies and Research, 2(7), 77-82.

Skackauskiene, I., & Vilkaite-Vaitone, N. (2022). Green marketing and customers’ purchasing behavior: A systematic literature review for future research agenda. Energies, 16(1), 456. doi:10.3390/en16010456

Szabo, S., Webster, J. Perceived Greenwashing: The Effects of Green Marketing on Environmental and Product Perceptions. J Bus Ethics 171, 719–739 (2021).

Vilkaite-Vaitone, N., & Skackauskiene, I. (2019). Green marketing orientation: Evolution, conceptualization and potential benefits. Open Economics, 2(1), 53-62. doi:10.1515/openec-2019-0006