In Japan, there is a dish called oyakodon (親子丼) which translates literally to “parent and child rice bowl.” The dish consists of both chicken and egg, hence the reference, and it is designed to satiate hunger on all fronts as a traditional, comforting meal packed with protein, fat, and complex carbohydrates.

Just as oyakodon (親子丼) harmonizes the flavors and nutrients of chicken and egg for a complete dish, so are individual action and systemic change required ingredients for the recipe of a sustainable future. One creates the other, but at the same time one becomes the other. Today we will focus on “the egg,” individual behavior change, to understand some of the psychological challenges that can spoil environmental action.

Serving Up Green Eggs & Habits

Social scientists are playing an increasingly vital role in hastening the shift toward a greener future. Their key objective: devise strategies to break down psychological, emotional, and social barriers to adopting more sustainable choices.

As a foundation for their work, the theory of reasoned action states, “consumers act on behaviors they believe will create or receive a particular outcome.” Though seemingly straightforward, this relationship leads us to wonder why green consumption is viewed as an exception rather than an expectation.

This article will explore leading theories and principles of human behavior change to answer these core questions.

The Purchaser’s Dilemma: A Battle Against Short-Sightedness

One universal truth important to behavior change science is that our species is instinctually short-sighted. In the primal quest for immediate gratification, we often find ourselves trapped in addiction and indulgence (e.g., alcohol, food, shopping, sex, social media). Therefore, any situation creating a delay in instantaneous pleasure for potential long-term benefits becomes especially challenging.

In statistics and economics, a related concept known as the prisoner's dilemma prevails. This idea suggests that, when all is considered, humans tend to prioritize short-term personal gains over long-term collective well-being. Such individualistic thinking has coddled environmental disasters for decades, contributing to global natural resource depletion.

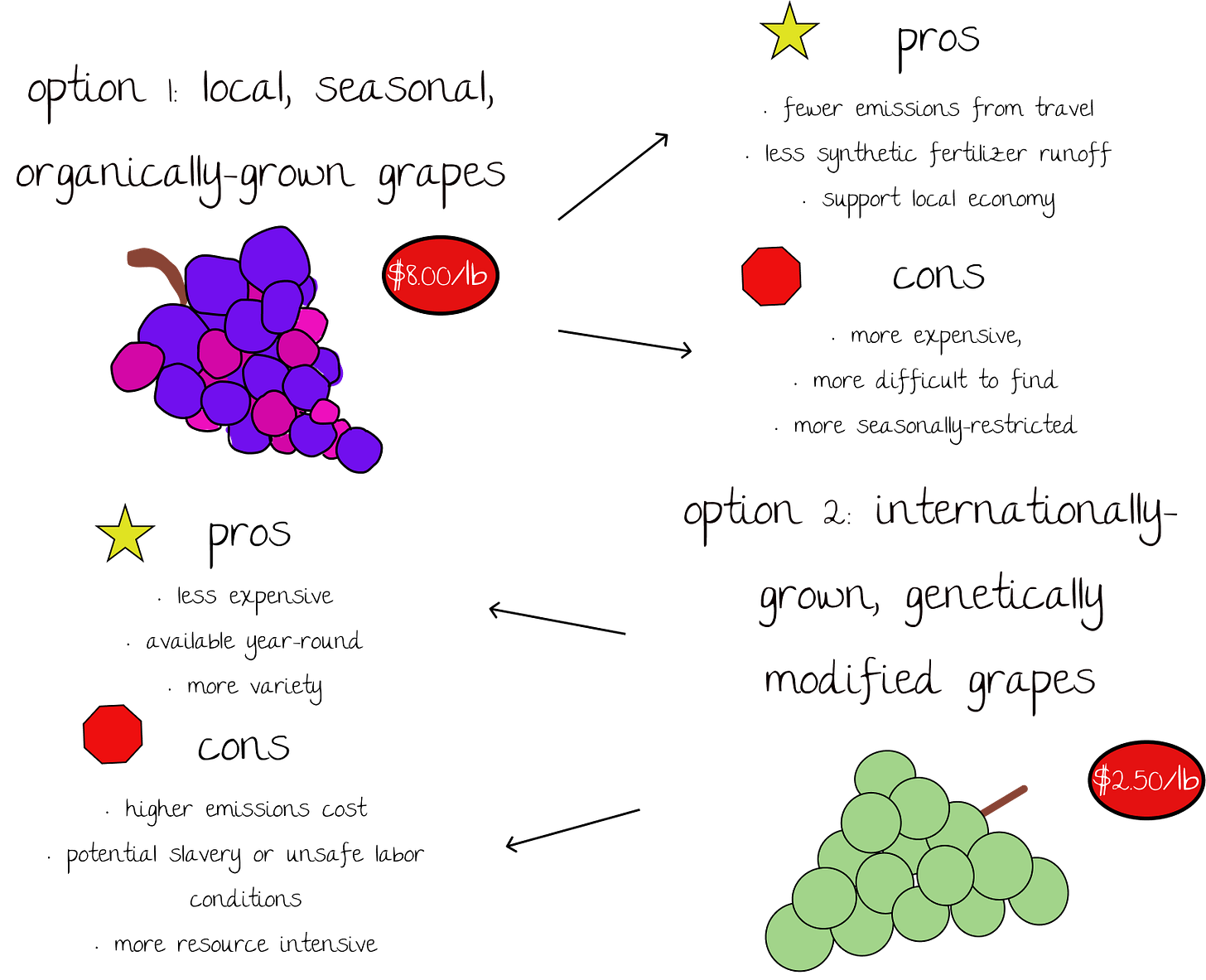

Though the prisoner's dilemma is commonly applied on a macroeconomic scale, sometimes referred to as the Tragedy of the Commons, it also operates at the individual level. I explore this notion further in the second chapter of my book, where I've coined it "The Purchaser's Dilemma." Let's explore this idea through the example below:

In today's climate, where decisions revolve around dollars and cents, most consumers are primed to select option 2 (which has higher social and environmental risks and a significantly lower price). Despite knowing that resource-intensive, disposable, and environmentally disruptive goods may harm our planet, we tend to favor the benefit to our pocketbook today rather than the benefit for our planet tomorrow. This psychological phenomenon is just one of the many hurdles in the way of conscious consumerism.

The Green Bubble: A Conflict of Identity

In addition to moment to moment instincts, deeply rooted cultural identities can also misguide us from the green path. For centuries, the western world has embraced the role of consumers, hailing consumption as the backbone of economics and the defining feature of the twentieth century. Pre-World War I consumers were once granted unprecedented political and civic power, and although privileges faded the pride persists.

Adopting the *heavily normalized* and *highly praised* consumer mindset causes us to accept ourselves as passive takers rather than changemakers, swimming aimlessly in the vast sea of capitalism. We see ourselves as participants rather than drivers in the market, and we are content with the degree of choice that is presented to us.

*Conscious* consumers, on the other hand, break free from this identity, entering what I like to call the Green Bubble. In this proverbial space, they are self-empowered to advocate passionately, build connections, and learn continuously about the products they choose to buy and the companies they choose to support. As environmentalism gains mainstream traction, more people proudly identify with this group and refuse to accept injustices associated with complex supply chains (e.g., climate change, plastic pollution, slave labor, animal cruelty, etc.).

Without that intent to learn more and vote with our dollar to reduce our personal contributions to environmental issues (a.k.a. the average consumer default), the likelihood of systemic change dwindles.

The Communication Conundrum: An Optimistic Challenge

The first two barriers lie within ourselves, but let's not dismiss the power of interpersonal communication and socialization.

Unfortunately, “doom and gloom” is the native language of environmental concerns. Think Greta Thunberg’s “Our House is on Fire” speech.

This is not to say that urgency and alarming tones are not warranted, but absolutism (i.e., all or nothing attitude), generalism (i.e., lack of specificity or actionality), and pessimism overwhelm audiences more than anything else, creating a feeling of universal helplessness.

The most effective modes of communication are actually the exact opposite. Relatable storytelling, solutions-oriented messaging, and highlighting scientific uncertainties ignite receptiveness to existential topics, unlike the chronic pessimism currently dominating our media landscape.

Every time the climate crisis is communicated as “an inevitable threat to humanity and the planet as we know it,” a shred of optimism for effective change dies.

My goal in sharing this information is to help bridge the gap between citizens and science in pursuit of a more sustainable future. It is critical for educators and activists to be conscious of not only what they are teaching, but how they are teaching it. This requires a baseline understanding of the human psyche and the challenges hardwired into our neural circuitry which might prevent us from internalizing and acting in accordance with climate and environmental science. Consider these three barriers when you are trying to change someone’s mind in any capacity, but especially for the betterment of our planet.

Question of the Day: For those of you who have tried educating a family member, friend, classmate, or community member on an environmental issue you care about, what hurdles have you run into? What worked or didn’t work? Did your efforts result in behavior change, and if not, how would you do it differently this time knowing this information?

P.S. As a sustainability buff, I know that this space is somewhat siloed and constantly evolving. Being said, I welcome your fact-checking and feedback! Working together to improve our collective understanding of sustainability is the goal of my page!

P.P.S. The views in this article are my personal perspectives and do not necessarily reflect the view of my employer or any other person or entity.

Connect with me on LinkedIn & subscribe to my Substack.